“

...as evaluators who apply judgement to evidence and data, we need to explicitly consider whose values are driving overall evaluation focus, questions and design. Similarly, in choosing methods of data collection, it is important to consider what evidence/data is being prioritised and why.

ESA Director Linda Kurti and Associate Director Julian Thomas presenting at the 2015 AES International Conference in Melbourne.

Making evaluative judgements about program outcomes is known to be an inherently values-laden exercise, yet conscious examination of the values influencing program and evaluation design is not always evident. The values held by those designing programs and commissioning evaluations are often poorly articulated, yet these values influence the definition of program outcomes, how success is conceptualised, and which forms of evidence are given greater credence.

Similarly, evaluation practitioners bring their own values to bear on the development of evaluative questions and methods, the interpretation of data and the generation of findings and recommendations.

The values held by stakeholders in our evaluation work are deeply influential to their perspectives on what matters and what information gets priority.

For example:

- if a key value is fairness, then you may ascribe more value to procedural fairness than to ‘cost effective’ and efficient processes

- if a key value is entrepreneurialism, then you may ascribe more value to innovative practice than to evidence-led practice

- if a key value is liberalism, then you may ascribe more value to clients’ exercise of choice than to intervention outcomes

- If a key value is positivism, then you may ascribe more value to measurable KPIs within a defined time frame than to the story or narrative.

Linda and I reflected on a typical scenario for evaluators which illustrates the multiple values frames which are relevant to our practice.

Independent evaluators exercise judgement about programs designed/delivered by providers for beneficiaries and commonly on behalf of funding organisations who are commissioning evaluation in compliance with accountability requirements established by third party central agencies.

Consider, for example, a program targeting Aboriginal children, delivered through a public hospital, and evaluated by a commercial evaluator for the Department of Health to guidelines established by Treasury.

We also explored two ‘case studies’ of value frames influencing evaluative practice.

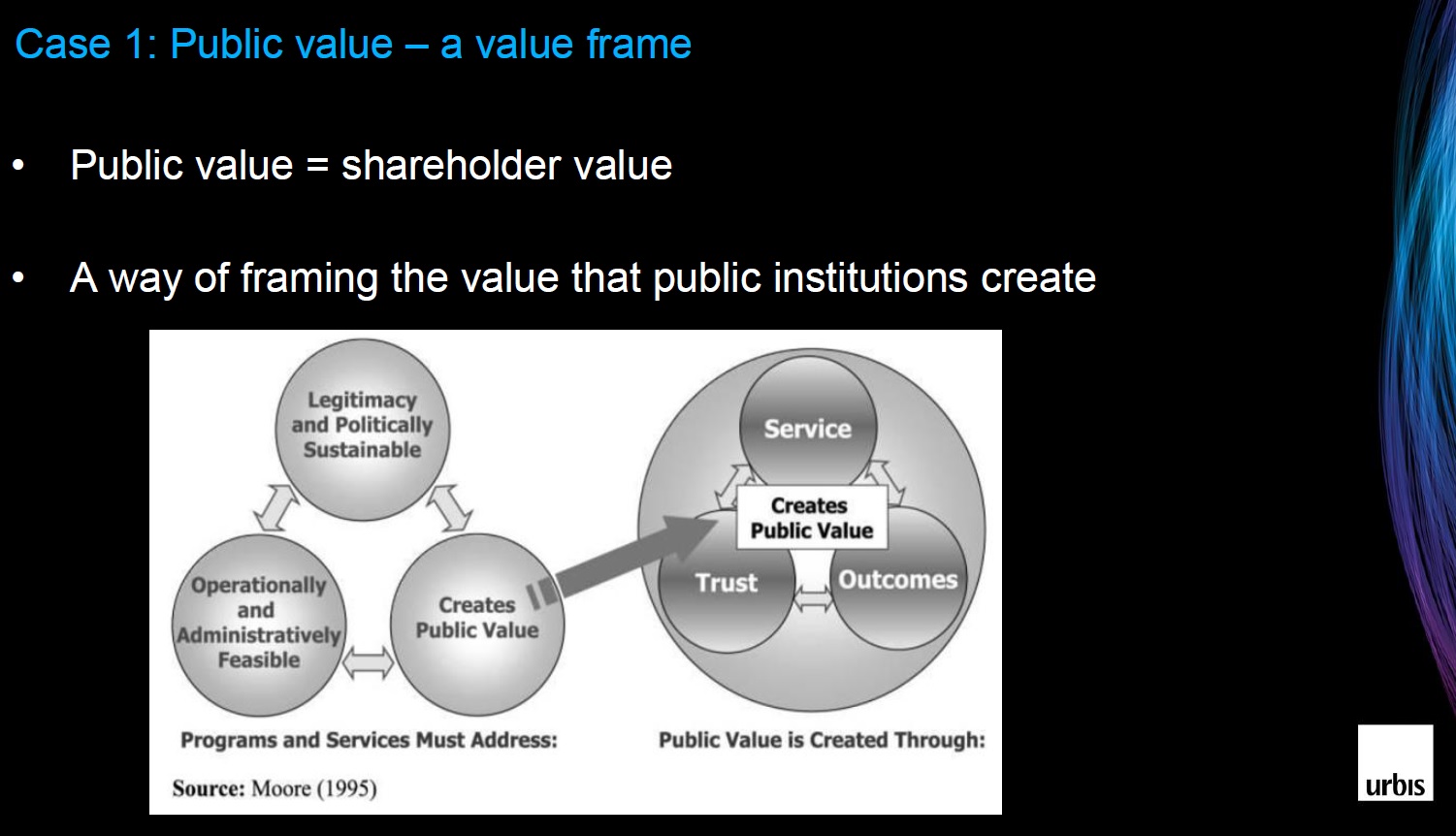

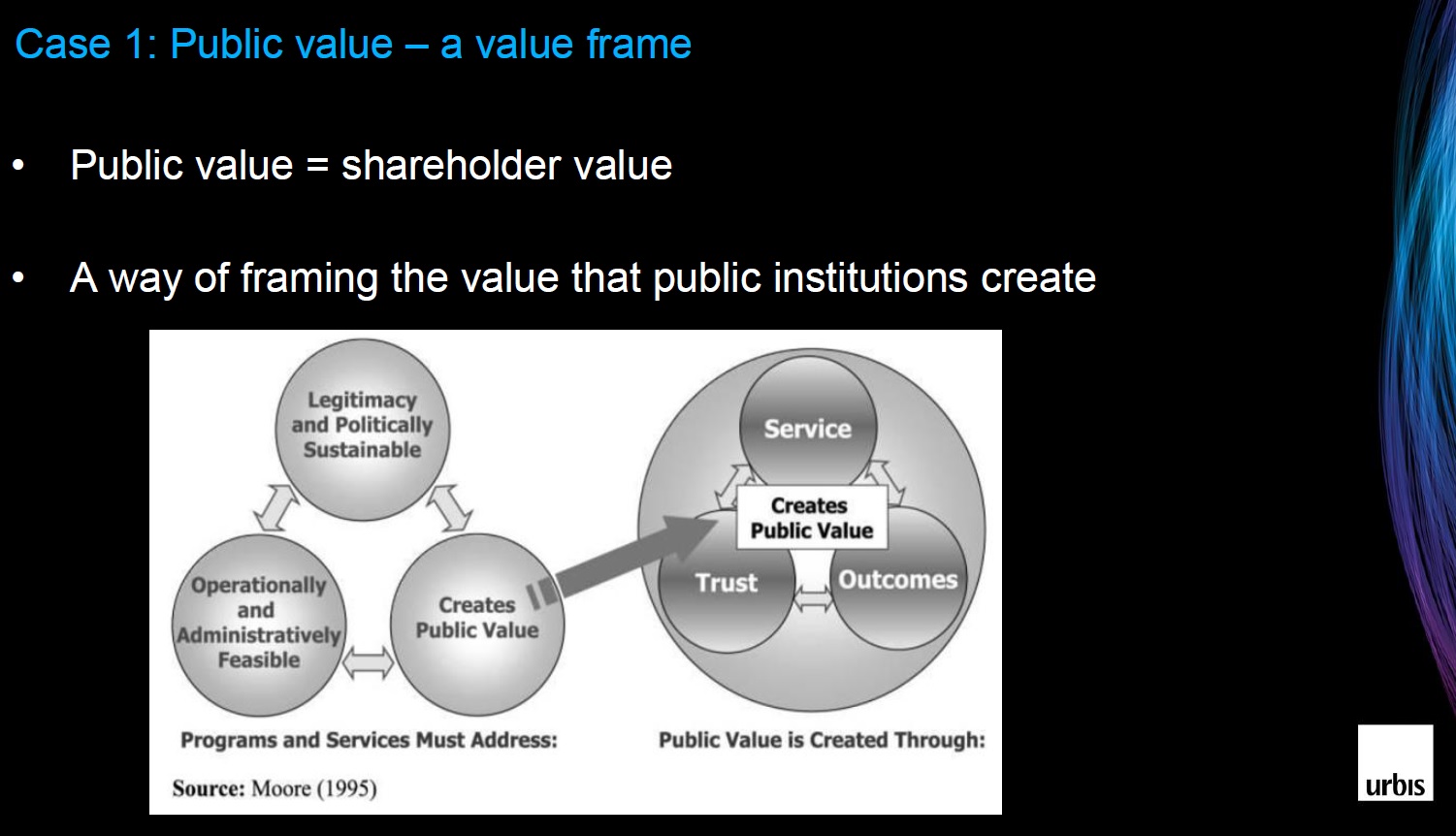

The first was the concept of Public Value developed by Mark Moore.

Public Value is the value created for the public by public institutions, and is analogous to shareholder value in a corporate setting. The idea of public value gives prominence to trust, service and outcomes.

The Public Value paradigm illustrates difference in business vs public service in the values held (commercial vs social) and the value generated (financial vs socio-political). For example, fairness and procedural justice are generally not commercial values but central to public service – this has implications for the focus of evaluative effort.

Our second case study looked at the Social Return On Investment (SROI) approach to measuring value creation.

Traditional cost-benefit analysis (CBA) implicitly gives more weight to readily measurable economic metrics (avoided future costs; lifetime earnings; carbon emissions etc). SROI is a form of cost-benefit analysis which expands CBA scope to place emphasis on capturing social and beneficiary defined value.

While both SROI and CBA provide a ratio of value to cost, the use of different approaches to determine what and how value is included in the calculations reflects a difference in the underlying values frame that is informing an evaluator’s choice of data collection method.

Ultimately, we argued that as evaluators who apply judgement to evidence and data, we need to explicitly consider whose values are driving overall evaluation focus, questions and design. Similarly, in choosing methods of data collection, it is important to consider what evidence/data is being prioritised and why.

Doing so will strengthen the legitimacy and transparency of evaluation.

Click here to download a copy of the presentation

This is an adapted version of a paper presented at the Australasian Evaluation Society (AES) conference, entitled ‘Drawing out the values’, co-presented with Director Linda Kurti, in Melbourne on 6 September 2015. This article originally appeared on LinkedIn.

For more information on our Economic and Social Advisory experts see below.