When you close your eyes and picture your happy place what do you see? For me I am somewhere near water. Running along the foreshore, immersing myself in cold water, or standing in a secluded part of the beach at sunrise taking in the smell and sounds of the ocean.

Living near water has long been central to Australia’s social identity, with the often-quoted figure of 85% of the population living within 50km of the coast.1 The coast continues to be the dominating image of Australia that we see locally, as well as the image which is projected internationally. The other central element of our identity is the pool, whether this is the local aquatic centre or the ocean pool. The coast and the pool are key social gathering places and remind us of the memories of swimming carnivals, catching a wave in the ocean, swimming recreational laps, or paddling in the ocean with family to escape the heat of summer.

The importance of the water to Australian identity became even more clear during the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated series of lockdowns, as we all sought refuge in our outdoor spaces. While there was a wave of attention on green open spaces, the tide has started to turn with more awareness on the importance of this counterpart to green space – blue space. The Sydney lockdown in the second half of 2021 saw blue space at the centre of political debate. The images of people swarming Bondi were met with uneasy feelings of double standards by communities in COVID-19 hotspot areas. The inequitable access to water led the former NSW Premier to open public pools across Sydney to the vaccinated in late September before many other restrictions were eased. For many suburban residents this announcement was met with relief. While much has been taken from us during this pandemic, it seems, access to water was too great a loss to bear. The first plunge into our local pool or visit to our favourite beach was welcomed across the city and become one of our first glimmers of hope on the horizon of the freedoms to come.

Defining Blue Space

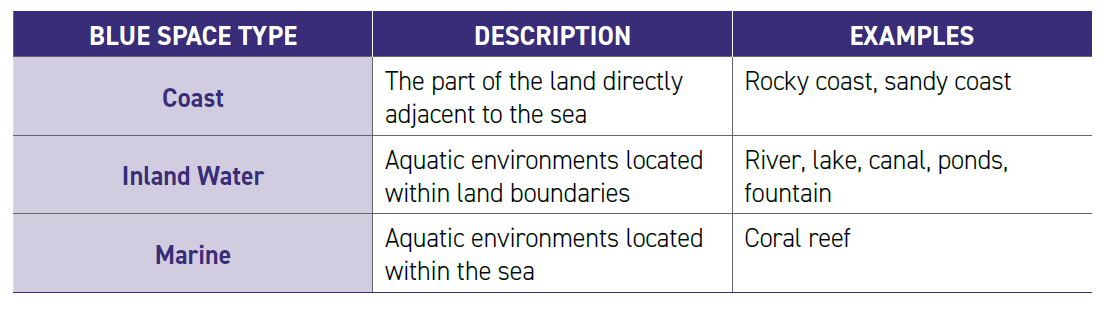

From an academic perspective, much of the blue space research has focused on natural marine and coastal settings, with some focusing on rivers, canals, and lakes.2 In its recent systematic review of research into blue space, the World Health Organisation (WHO) found three categories: the coast, inland waters and marine environments.3 BlueHealth, a pioneering European research project which investigated the links between urban blue spaces, climate, and health, defines urban blue spaces as fountains, lakes, rivers, and coastlines.4 The pool is not included in BlueHealth or WHO definitions of blue space, likely due to it being a form of hard infrastructure, rather than natural space. However, pools arguably have similar positive psychological impacts on wellbeing as natural spaces.

The benefits of blue space on health and wellbeing

The United Nations projects that by 2050 two thirds of the world’s population will live in urban areas.5 Julia Baird in her book Phosphorescence, poetically wrote “more and more of us will become deprived or starved of nature, will spend days and months without glimpsing an expanse of green, a stretch of blue or an uninterrupted horizon, and will surely experience, as a result, a kind of unidentified ache or restlessness”.6 It is widely understood that access to green space has many positive impacts on our psychological wellbeing. The impacts of blue space, however, are less understood. This is despite Infrastructure Australia’s Infrastructure Audit 2019 report, which includes “green space, blue space and recreation”7 as one of six social infrastructure categories that people should have access to. In Infrastructure Australia’s 2021 report, access to blue space was again recognised as key social infrastructure that improves physical and mental health and make communities more liveable.8

The lack of research on blue space is highlighted in WHO’s Green and Blue Spaces and Mental Health: New Evidence and Perspectives for Action (2021). Two systematic reviews were undertaken, one on green space and one on blue space. A search found 16,851 unique papers on green space compared with only 25 unique studies on blue space. Of the latter studies, most focused on coastal exposure, with very few looking at inland water systems. This research found that studies looking at coastal exposure, as opposed to just coastal availability or proximity, in general showed more consistent positive results on mental health.9 Of the different mental health and wellbeing outcomes looked at in the studies, the most profound effects of blue space were found for affect (an individual’s immediate expression of emotion), restorative outcomes and perceived stress. Other benefits of blue space were created by the visual openness of the space and fluidity of the water.10 By comparison, the studies looking at green space found that the most pronounced effect was on affect (an individual’s immediate expression of emotion), followed by vitality and restorative outcomes. This shows there is some evidence that blue space has distinctive benefits on health and wellbeing when compared to green space, however more is needed to fully understand this.

Creating more access to blue space

There are no known recommendations around the amount of desirable blue space per person, minimum size or accessibility requirements, like the commonly referenced green space principles developed by the Government Architect of NSW.

To assist urban planners, landscape architects and other relevant professionals, BlueHealth researchers developed a novel tool to identify whether a particular blue space has more opportunities for obtaining greater access to water. Using this tool, BlueHealth undertook several small-scale interventions including a project in Plymouth in the United Kingdom. Working with the local city council and Wildlife Trust, BlueHealth identified an area of inner-city beach to regenerate and improved access to the water through several design interventions. This included providing a stepped open-air theatre to the water for community gathering, better landscaped areas, provision of grassland and seating with open views to the water. Improvements were also made to the water slipway to enable easier and safer access for water-based recreation activities. BlueHealth found that these small interventions increased activation in this area, improved local health outcomes and had a positive impact on people’s psychological wellbeing.

In conclusion

Blue space is critical social infrastructure that many of us love and crave. While there has been limited research in this field, the research that has been undertaken shows that blue space has distinctive characteristics and benefits. These include the visual openness and movement of the water and its ability to reduce our perceived feelings of stress. There is a need to better understand the benefits of blue space, and to implement principles, like that of the Government Architect’s green space principles around access, quality and quantity to create a wholistic social infrastructure story.

Isabelle Kikirekov MPIA is a Senior Consultant in Urbis’ Community Planning team, specialising in working with the public and private sector to consider social outcomes, opportunities and impacts of planning and development. Isabelle believes that having equitable access to social infrastructure and open space is the key foundation for a successful place.

Endnotes

- See: https://blog.id.com.au/2014/population/demographic-trends/how-centralised-is-australias-population/

- The World Health Organisation (WHO) 2021, Green and Blue Spaces and Mental Health: New Evidence and Perspectives for Action, WHO, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Ibid

- See: https://bluehealth.tools/2020/09/13/blue-profile/

- See: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html

- Baird, J 2020, Phosphorescence, HarperCollins Publishers, Sydney

- Infrastructure Australia, 2019 An Assessment of Australia’s Future Infrastructure Needs, Australian Government, Australia.

- Infrastructure Australia, 2021 Reforms to meet Australia’s future infrastructure needs: 2021 Australian Infrastructure Plan, Australian Government, Australia.

- World Health Organisation (WHO), 2021 Green and Blue Spaces and Mental Health: New evidence and Perspectives for Action, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen.

- Ibid.

This article was originally published by the Planning Institute of Australia.