The land supply crunch in Melbourne’s industrial heartland

With Melbourne Australia’s second most populous city and growing, what are the solutions? Urbis Partner Shane Robb, with input from Eleni Roussos and Brenton Reynolds, explores.

A persistent shortage in Melbourne’s major industrial precinct

As far back as 2018, an Industrial Land Supply Research Report that Urbis completed with the Property Council of Australia (PCA) demonstrated a significant shortage of developable industrial land in Melbourne’s industrial heartland, the western corridor. Urbis and PCA updated and completed the same report in 2022, and found the shortage was persisting.

Melbourne’s Western industrial heartland represents around 55 percent of all large format warehouses developed over the past ten years. It is home to almost every major industrial corporate occupier, including the supermarkets (Woolworths, Coles, Aldi and Metcash, the latter two developing new premises of 100,000m2 and 115,000m2 respectively); major retailers (including Kmart, Target, Pacific Brands, Myer, Mitre 10 and Super Cheap); e-commerce groups (Amazon, Vida IXL and Kogan); transport/third-party logistics (3PLs) (DHL, Ceva, Toll, Linfox) and general industry (Fosters, Visy, Murray Goulburn, Gam Steel and AWB).

Signifying the economic importance of the area, the Victorian state government has committed more than $10B to building the West Gate Tunnel, targeting the transportation of circa 3.4 million inbound twenty-foot equivalent (TFE) containers from the Port of Melbourne into this industrial precinct. Most imports to Melbourne are warehoused and distributed from this precinct. But what about the supply of land?

Land take-up and the growth of data centre demand

The Victorian government stopped publishing its Urban Development Program (UDPs) land consumption and available supply reports in 2022.

However, in the last report, the past five years of the data set showed a Western Region land take-up average of c175 hectares, almost thirty percent higher than the five years prior, with the last year of the data showing almost 230 hectares of take up. Since 2022, built form supply has continued at a rapid rate and to adopt an annual average volume of say 250 ha would be reasonable, if not perhaps conservative.

As population grows, this rate of take-up is only expected to increase. In addition, there has been an explosion of demand for industrial sites in the western corridor, from the major data centre players who once sought sites in the 2-4 ha range; but current day artificial intelligence (AI) demand expectations have site size objectives sitting at 10ha plus.

Most of this take up in the west has occurred in the industrial precincts between the Western Highway (to the north) and Leakes Rd (to the south).

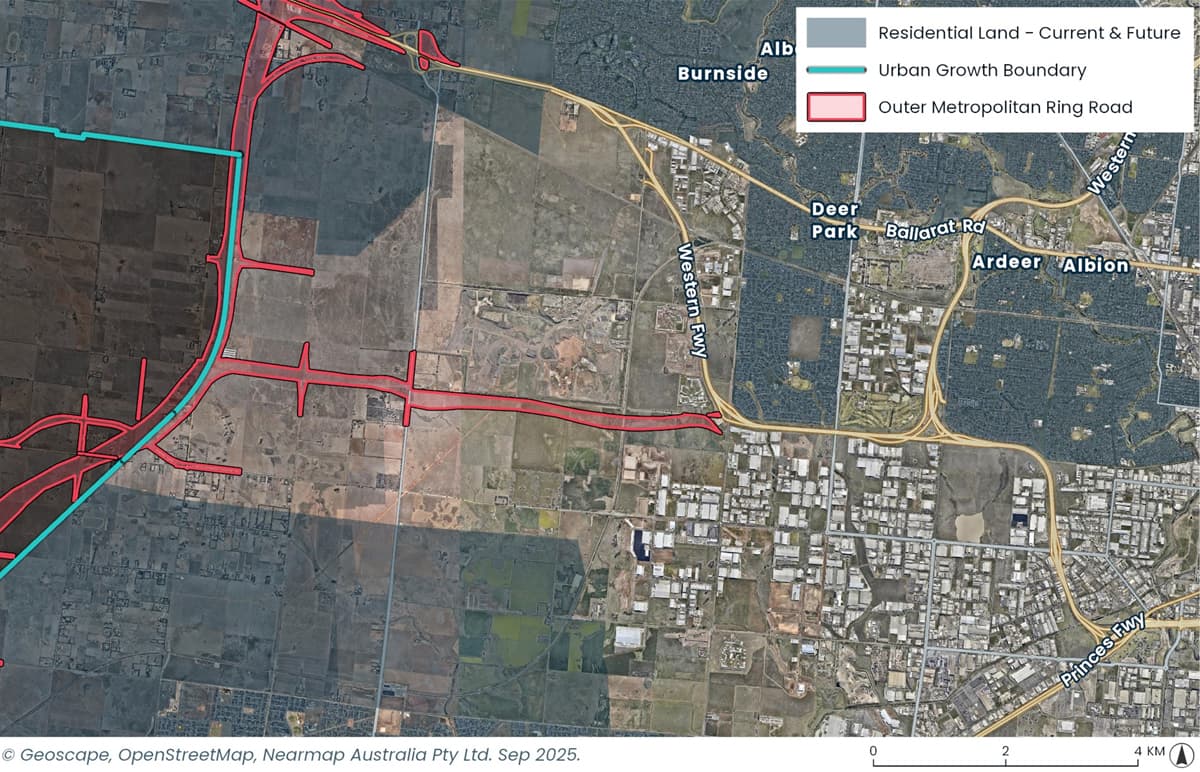

The below maps demonstrate the buildings added over the past decade:

The maps show that the Urban Growth Boundary (UGB)), a designated metropolitan boundary for Melbourne, last changed in this location in 2011 and to do so, required majority vote in both houses of parliament to agree to a change.

In the western corridor, the proposed Outer Metropolitan Ring Road (OMR) aligns with the UGB. Notably, the land west of the UGB/OMR forms the Declared Western Grassland Reserve, eliminating the potential for future expansion of the UGB to provide for additional supply.

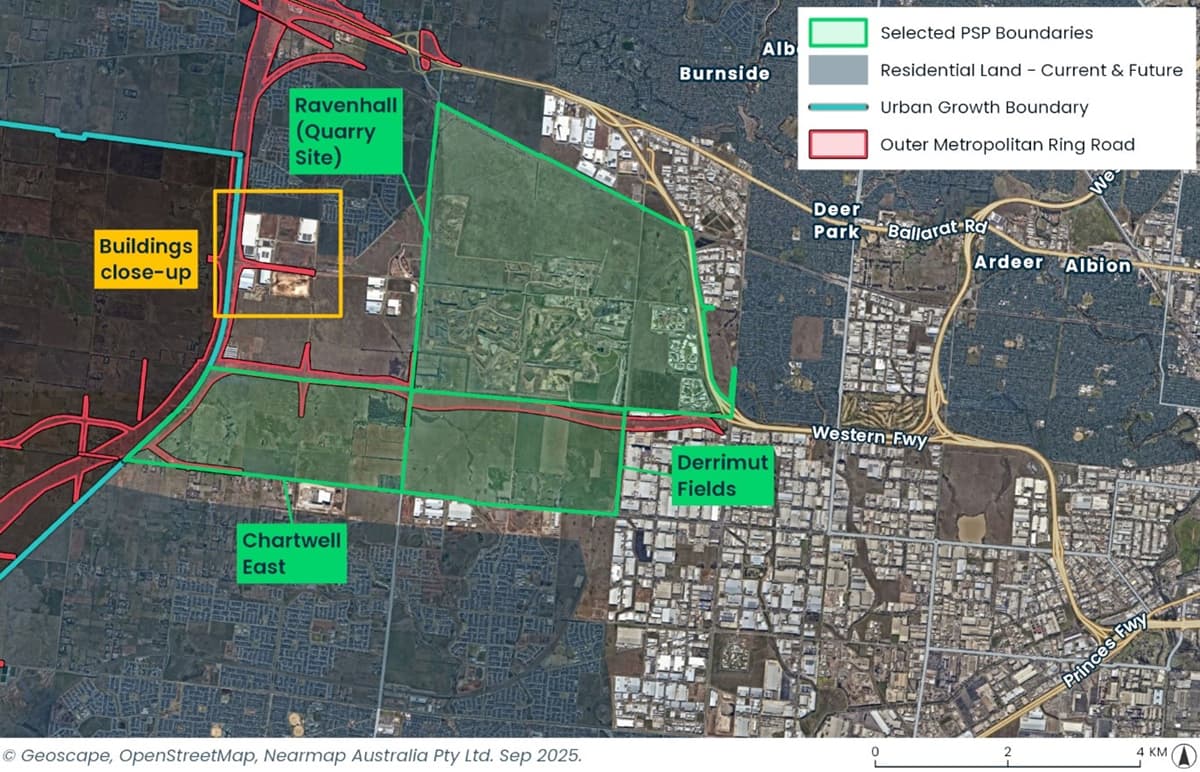

The below image zooms in to show the recently completed Metcash distribution centre, Super Retail Group, and some specs by ESR/Barings which, combined, sit virtually next to the UGB and future OMR (i.e., the outer most boundary for industrial development in this precinct.)

Precinct Structure Plans (PSPs)

The employment land PSPs, all sitting within the recently announced Horizon 2 and 3 on the city side of the proposed OMR, are limited to Derrimut Fields (519ha – H2), Chartwell East (548ha – H3) and Warrawee (138ha – H2) totalling around 1,205ha. Allowing for the Western Interstate Freight Terminal (WIFT) currently designated for within Chartwell East and estimated at 200ha, this reduced the total to around 1,000ha.

Where to from here?

Accepting there may be at best two-three years supply in the market, the implications are that the above PSPs will only add circa four years supply, and in any event these Horizon 2 PSPs are only expected to commence between 2025-2029, with Horizon 3 dates being 2029-2034. Does this mean that within five years, Melbourne’s Western Industrial Heartland will be virtually full?

The Market must therefore consider other locational options for industrial land:

- Outer west – into the Melton corridor

- Outer southwest – down towards Avalon and Geelong

- North – into the Mickleham & Beveridge corridor

- Brownfield – turn inwards back to Footscray, Tottenham, Altona, and find those larger sites that work, land contamination and site consolidation the greatest barrier to activation.

Development is already occurring in these corridors, but the extent of development will soon increase significantly. But which precinct will benefit the most? And is the road infrastructure/services capable of supporting this increased demand? Consider all the other implications, on infrastructure, planning and Net Zero targets.

How industrial precincts are becoming sustainable hubs

In terms of sustainability and ESG, industrial precincts are fast becoming the epicentres of the transition to Net Zero, acting as key enablers in the zero-emissions supply chain and wider net zero economy. Warehousing, logistics hubs and data centres can be energy-intensive and carbon intensive – both from an operational and embodied emissions level.

Without proactive sustainable planning and development, there is a strong risk of locking in long-term carbon impacts. Future ready sustainable industrial precincts incorporate precinct-scale net zero energy systems, low carbon and energy-efficient built forms, enable transport decarbonisation across the supply chain, and deliver broader community and social value.

Energy efficient, sustainable, resilient assets enhance the tenant and long-term asset value and market appeal, reduce climate risk exposure, and contribute positively to the environment, government and council sustainability targets, and surrounding communities. This includes integrating green space and biodiversity corridors, improving transport connections and active mobility options, and ensuring employment hubs support skills development and local economic opportunity.

By embedding circularity, governance and social value into industrial planning – alongside net zero and sustainability imperatives – these new sustainable industrial precincts can become not only efficient and low-carbon, but also sustainable places that generate economic, social and environmental benefits for occupiers and developers. Coordinated planning, infrastructure delivery and strong sustainable design principles will be essential to achieve these critical outcomes.

Moving forward – steps the state government is taking

The Victorian government has introduced a suite of new tools and pathways to facilitate industrial development. This recognises the importance of new employment land to complement the new communities being delivered in the growth corridors.

While these are new and untested, the recognition of streamlined pathways for delivering employment land recognises that employment PSPs has different needs to residential PSPs and ought to be able to progress with a bespoke set of requirements. Key for unlocking these will be the delivery of infrastructure and alignment in timing and funding of local and state items.