Homes at scale: how private and public power can deliver the Great Australian Dream

Changes are underway at the level of federal and state governments to address Australia's unrelenting housing crisis. But the challenge is to convert this momentum into delivering more homes for Australians. We consider how this objective could be achieved through an ambitious, two-pronged strategy:

Part one: Enable the private sector to build

The path must clear for private developers and builders to deliver more housing, through five key areas where policy intervention can unlock supply: planning and approvals, land availability, taxation, construction innovation, and workforce capacity. By addressing chronic delays, shortages, and disincentives in these domains, Australia can restore incentive and capability for the private sector to build the homes our growing population needs.

Elevate planning and construction processes

The challenge

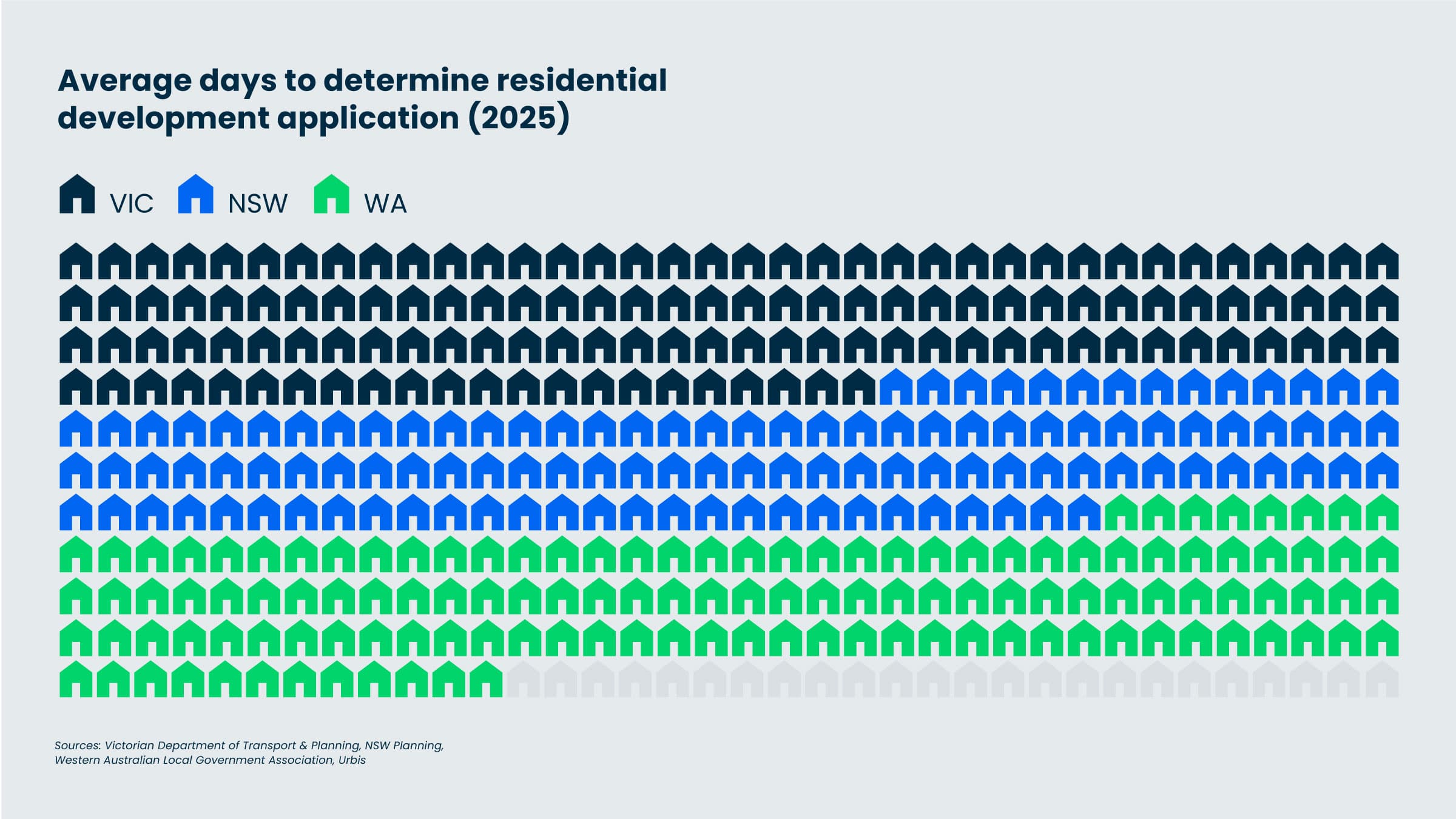

It is well-known that cumbersome and risk-averse planning processes and approvals stall housing projects nationwide. It can take more than a year to obtain a development approval for a subdivision – with up to seven months of that lost to unnecessary delays, according to the Housing Industry Association (HIA).

Complex layers of regulation, inconsistent codes, and low transparency increase cost and uncertainty for developers. The Productivity Commission recently identified slow planning and permitting as a primary factor behind Australia’s housing supply malaise.

How we can move forward

Despite the challenges, Australia is regaining momentum, and continually streamlining planning and building approvals can maintain this pace.

By cutting ineffective regulations and boosting efficiency in approvals, the time it takes for new housing to go from concept to construction will reduce. This is already happening - since the signing of the Housing Accord, planning reform has picked up pace nationally.

Further items that can contribute to this momentum include:

- Fast-track key developments - particularly for projects that address public needs, such as social and affordable housing, or that use innovative construction methods.

- Streamline processes - such as statutory time limits for decisions and removing duplicative steps that do not improve outcomes.

- Digital transformation - in planning agencies will help clear backlogs and provide certainty of delivery timelines, to support developer decision-making.

- Greater process transparency - such as clear criteria and live tracking for approvals will rebuild trust with industry, through improved certainty with process time-frames. Greater predictability of planning processes and time-frames will allow developers to make decisions with more confidence.

- Standardise codes - especially for emerging building technologies, such as modular construction, and pre-approving compliant designs can expedite projects. To maintain quality as rules are streamlined, regulators should adopt tools (such as independent building oversight and defect rectification schemes in New South Wales) to ensure faster approvals don’t compromise safety.

- Deregulate institutional land use frameworks - and empower public and quasi-public institutions with capital and the ability to act with intent over the long term (such as hospitals, universities and other community infrastructure), with pathways to develop housing on their land, supplying homes for students, staff and essential workers.

Unlock development-ready land

The challenge

Even when private appetite to build is strong, projects only proceed if land is available and appropriately zoned. Land use constraints exacerbate Australia’s housing shortfall – restrictive zoning, misaligned regional plans, and infrastructure that lags development. In fast-growing areas, the stock of development-ready land is insufficient, and outdated land use definitions prohibit diverse housing types (such as townhouses, mid-rise apartments, or granny flats) that modern communities need.

Earlier this year, a UDIA Report noted that in Sydney, only fourteen percent of zoned residential land is "shovel-ready” (vacant and unconstrained), due to infrastructure and planning limits. A lack of coordination between transport infrastructure and land release means suburbs often extend without adequate public transit. Conversely, constructing costly new rail lines through low-density areas rarely results in housing renewal, due to restrictive planning controls.

How we can move forward

Through strategic reform of land use controls, a lack of prepared land or infrastructure does not need to stand in the way of the new housing supply. The federal government recently announced it will fast-track the assessment of more than 26,000 applications under the EBPC Act consideration, and pilot artificial intelligence (AI) tools to simplify and accelerate assessments and approvals. Other potential activity includes:

- Support infill renewal through zoning reform - by aligning regional and metropolitan plans so that zoning reflects demand, enabling higher densities and mixed housing types in job-rich cities and suburbs.

- Unlock infill renewal through complementary reform - Melbourne faces a shortage of well-located housing, yet restrictive rules requiring unanimous owner consent for redevelopment lock older strata-titled sites into their current form. Urbis research identified over 1,000 such underdeveloped sites within 15 km of Melbourne’s CBD that could deliver more than 100,000 new dwellings if redeveloped. Unlocking this supply could include strata reform, such as reducing the consent threshold to 75 percent and adopting legislation such as NSW’s Strata Schemes Development Act. There exists a range of reforms that have the potential reduce friction in the system across the country.

- Lead with infrastructure to shape renewal - The federal government announced earlier this year it would work with states and territories to accelerate the delivery of planning, zoning, approvals, and investment in enabling infrastructure. Investing in new transport and services ahead of development can open land and drive private sector activity.

For example, adopting a station-led development strategy: building new train or transit stations in growth corridors and simultaneously zoning surrounding precincts for housing. This approach of aligning public infrastructure investment with precinct-scale private development can reduce cost and complexity in the long term. Alongside transport, governments can coordinate utilities and amenities delivery (roads, water, schools, parks) in growth areas, leveraging tools like value capture to offset infrastructure costs by tapping land value uplift. - Subsidise enabling infrastructure costs in growth areas - To accelerate supply, targeted public subsidies can offset upfront infrastructure costs in priority housing areas: for instance, subsidising enabling infrastructure in new greenfield suburbs or infill brownfield sites to make projects financially viable sooner. A recent example of such a policy is Queensland’s Residential Activation Fund, a $2 billion program that partners with local councils and the private sector to unlock development-ready land over four years. The fund specifically targets projects where a lack of essential infrastructure, such as water, sewer, or road connections has delayed delivery. By sharing the upfront infrastructure burden, the program aims to bring forward thousands of lots, across both greenfield and infill locations, increase the stock of shovel-ready sites, and smooth the pipeline of housing supply into the market.

- Proactively assemble fragmented land - Where land assembly is a barrier in identified growth areas – such as fragmented ownership preventing urban renewal – reforms to compulsory acquisition (eminent domain) could empower authorities to acquire and consolidate sites for housing-led redevelopment. Through coordinating the assembly of fragmented sites, higher quality design outcomes can come to life through unlocking the benefits of larger, precinct-scale sites.

- Subsidise feasibility in desirable projects - Finally, leveraging federal funding sources, such as the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) could de-risk and fast-track development-ready projects that are struggling to realise financial feasibility in the climate of high construction and finance costs. Long-term, predictable funding pathways give confidence to scale social, affordable, and market housing.

Support development through tax

The challenge

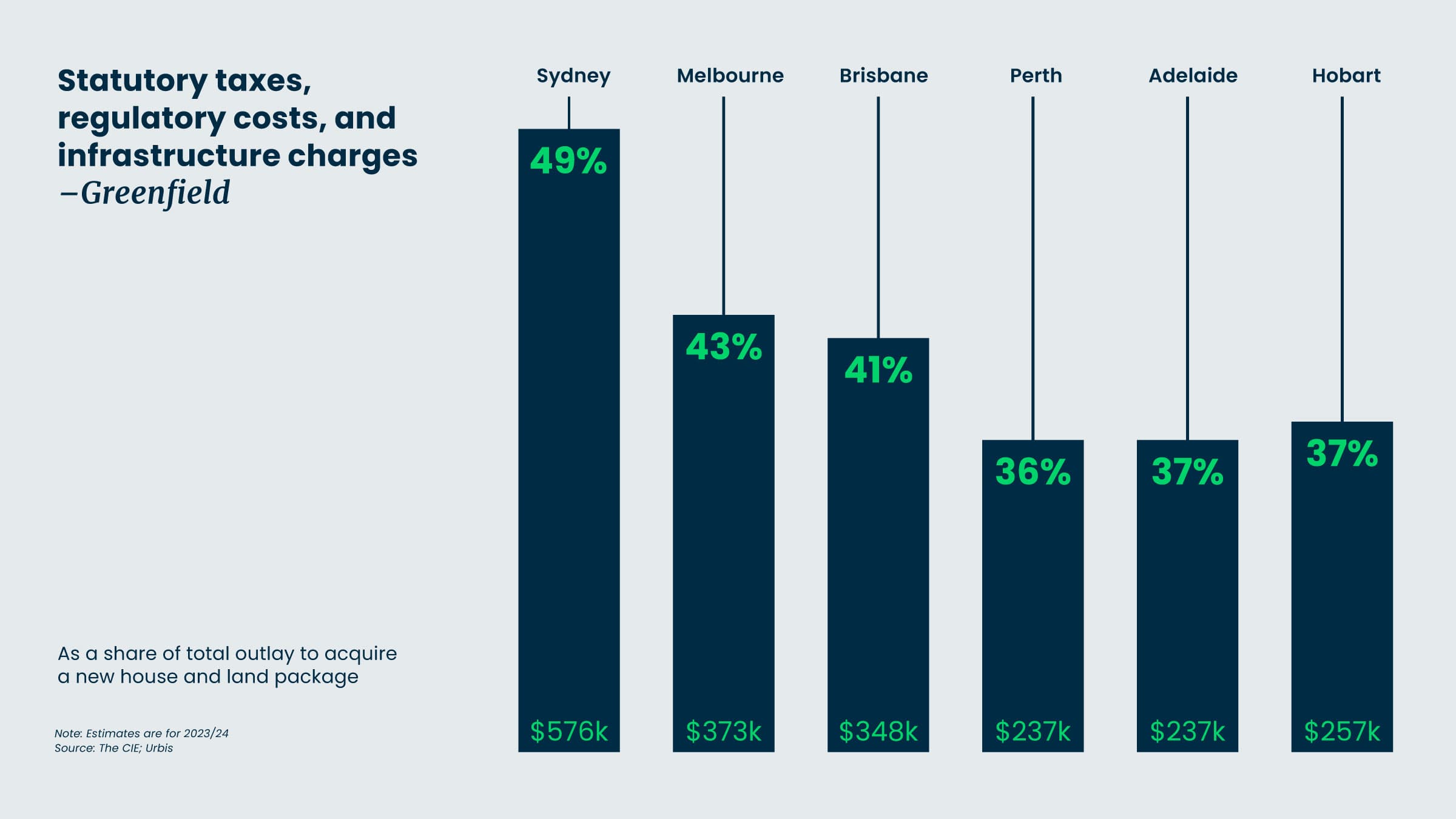

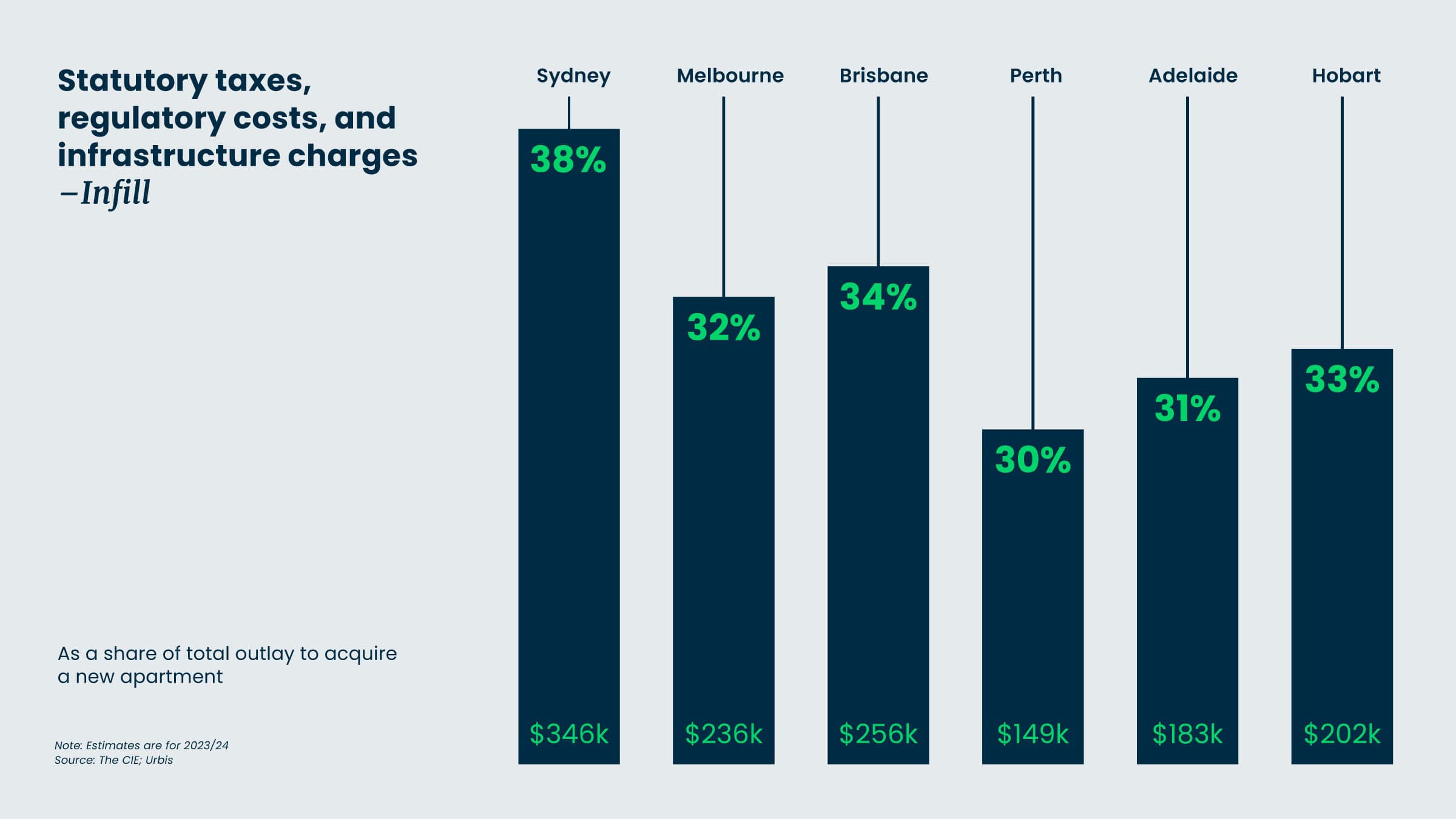

A complex web of taxes, charges and levies that significantly raise costs burdens housing construction in Australia. According to the Housing Industry Association, government taxes, regulatory costs and charges account for $346,000 – about 38% of the cost of a new apartment in Sydney. These added costs are staggering, often outstripping developers’ profit margins and making projects financially unfeasible. Worse, they have escalated rapidly: in Brisbane, the tax and regulatory cost component of a new apartment has surged by $104,000 since 2019.

This includes fees, infrastructure charges, planning levies, GST, stamp duties, and more. Such a heavy fiscal load discourages development (fewer projects can “stack up” profitably) and the burden passes on in the price of new homes, undermining affordability. Tax policy can also distort incentives – for example, hefty stamp duties discourage transactions and development, while narrow funding bases for infrastructure, pushing municipalities to rely on developer charges that further raise housing prices.

A more balanced approach would shift the burden away from taxes that penalise productive activity (including building new homes) and towards those that capture gains from passive asset holding. This would reward those bringing new supply to market, discourage speculative withholding of development-ready sites, and help align the tax system with the goal of increasing housing supply.

How we can move forward

Smarter tax policy can reduce the upfront cost burden on housing development and encourage investment in supply. A recalibrated tax system can boost housing construction by cutting excessive costs and by rewarding the kinds of development Australia needs most.

- Replace stamp duty with a land tax - Stamp duty is a notoriously large, upfront tax that impedes both buyers and developers. Currently, the tax system disincentivises productivity through rewarding land banking. Transitioning from stamp duties to a broad-based land tax (or an expanded land value capture system) would spread the revenue base and remove the disincentive on property turnover. Such a shift, combined with other broad tax base measures, can fund infrastructure in a more efficient, equitable way than lump-sum levies on new homes.

- Reform infrastructure charges - by capping or waiving certain infrastructure charges for projects that deliver public benefits like affordable housing or infill development. Tax incentives could also be used to spur innovation and affordability – for instance, providing targeted tax credits or rebates for projects using Modern Methods of Construction (MMC), to offset initial setup costs for modular manufacturing or for developments that include a significant portion of affordable or social housing.

- Encourage Build-to-Rent through tax reform - The private Build-to-Rent (BtR) sector, which offers professionally managed rental housing at scale, should be encouraged through tax settings: recent moves to allow accelerated depreciation (four percent capital works deduction) and reduced withholding tax for eligible BtR projects are steps in the right direction, as are land tax discounts some states offer for BtR.

According to Urbis’ Apartment Essentials Platform, there are over 49,000 Build-to-Rent units in the pipeline nationally. While funding remains a challenge, Urbis estimated that almost half (45%) of these units are funded with the balance currently seeking capital partners.

Align federal and state tax policies

States are highly dependent on property taxes (stamp duty, land tax) while the Commonwealth controls income tax, GST and migration policy, leading to mismatched incentives. A national framework on development taxes and infrastructure funding could ensure all levels of government pull in the same direction to lower the effective tax on new housing.

Embrace Modern Methods of Construction (MMC)

The challenge

Australia’s construction industry lags international peers in adopting modern methods of construction – such as off-site prefabrication, modular assembly, and advanced manufacturing techniques. This lag is reflected in stagnating productivity: the Productivity Commission found that the number of houses built per hour of work has more than halved in the past 30 years, and overall labour productivity in home building has declined by 12%. By contrast, other sectors and other countries have achieved efficiency gains through innovation.

Dwelling construction productivity is in decline

In countries such as Sweden and Japan, modular and industrialised construction account for a substantial share of housing delivery. Off-site construction accounts for just five percent of Australia’s new housing, compared with over 15% in countries such as Sweden, Singapore & Japan - bringing consistency and economies of scale – whereas Australia remains mostly project-by-project craft construction.

The slow uptake of MMC and digital technology was singled out as one of four key factor in our housing sector’s “decades of poor performance”. In short, building homes in Australia remains a traditional, labour-intensive exercise, undertaken by small firms with little incentive for standardisation – a recipe for prohibitive costs, delays, and vulnerability to skill shortages. Without change, the construction sector cannot scale up to deliver the homes we need at the required pace.

Embracing MMC not only promises faster, cheaper building, but can also improve quality through factory precision. It is also a way to tackle workforce constraints: manufacturing housing off-site can attract a more diverse labour pool and use automation to alleviate skilled trade shortages. A concerted push for modern construction methods – through public investment, procurement preferences, regulatory reform, and training – can sharply improve the efficiency of building new homes, increasing the likelihood of achieving ambitious housing targets.

How we can move forward

Driving a step-change in construction innovation will be crucial to boost productivity and output. The federal government’s recent announcement that it will pause and streamline the National Construction Code (NCC) until mid-2029, to consult with stakeholders in how barriers to modern methods of construction (including prefab and modular housing) can be removed, is a huge step towards seeing this solution implemented.

- Public sector-led MMC programs - such as governments (or government-backed housing corporations) commissioning large volumes of prefabricated social housing or partnering with modular construction firms to deliver schools, hospitals, and housing. This guaranteed pipeline can justify investment in new factories, techniques, and upskilling the workforce. Preferential procurement policies should reward bidders that use modular or off-site construction with proven time /cost savings – effectively using public projects to kick-start the MMC industry.

- Subsidies and tax credits - for establishing off-site manufacturing facilities, or financing schemes that help developers with upfront costs of modular approaches, would address current barriers.

- Regulatory reform to support standardisation - in areas like insurance, warranties and building codes is also needed to normalise MMC: for instance, updating building regulations to accept pre-approved modular components and working with insurers to ensure new methods can get coverage and financing on equal footing with traditional builds. Standardising designs (e.g. template modules for apartments or student accommodation) and promoting open-source design libraries could further reduce duplication and cost.

Grow the construction workforce

The challenge

Even with improved processes and technology, housing supply depends on people – builders, tradespeople, architects, and engineers. Australia faces a critical shortage of construction workers and skills. Despite a 25% increase in the construction workforce since 2013, those workers are collectively producing 25% less output (in terms of housing units) compared to a decade ago. In 2021, women made up less than five percent of construction trades. We simply don’t have enough skilled workers to design and build at the scale required, and those we do have may be underutilised or hampered by outdated practices.

Training pipelines are struggling – apprenticeship uptake and completion rates are low and not keeping pace with retirements. Rigid occupational licensing and siloed trade specialisations make it difficult to deploy labour flexibly where needed. Moreover, competition for labour from major unionised infrastructure projects (roads, rail, mining) pulls workers away from housing construction. If unaddressed, this workforce bottleneck will be a ceiling on any housing acceleration plan.

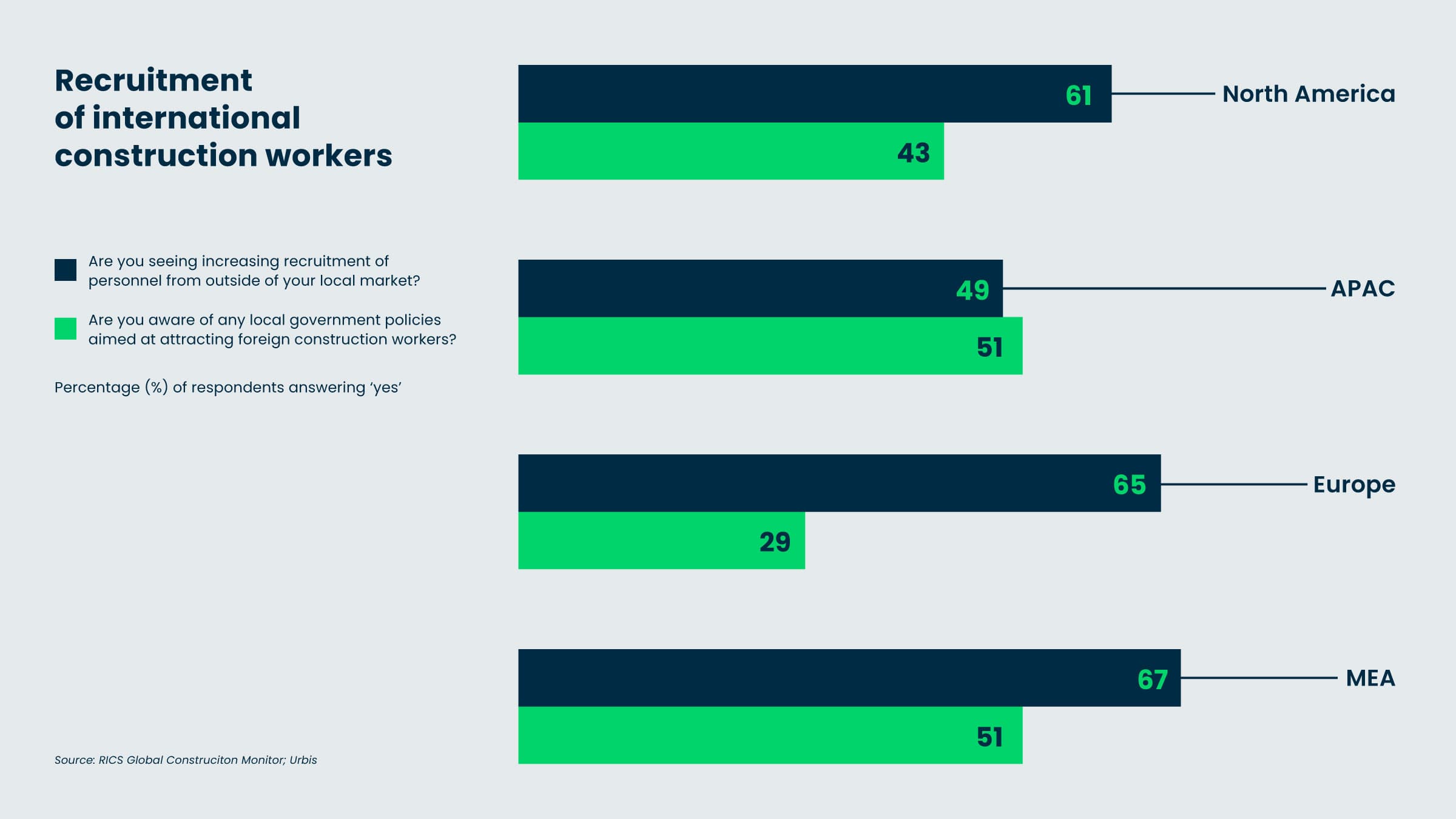

It is not just an Australian problem; it is a global issue. Skilled labour shortages remain a defining challenge for the construction industry, continuing to drive up costs worldwide. Globally, 71.7% of markets report persistent skills shortages. In many advanced economies, housing shortfalls are adding further complexity — limiting the capacity to attract and accommodate additional workers, even where demand for labour is strong. In this context, competition for global construction talent is intensifying, with markets increasingly vying for the same limited pool of skilled workers to deliver critical housing and infrastructure projects.

How we can move forward

A multifaceted strategy can grow and upskill the construction workforce. By investing in people alongside projects, Australia can ensure we have the human capital required to build the homes we need.

- Target skilled migration - Skilled migration can provide immediate relief: Australia should streamline visa pathways for construction-related occupations (from engineers to carpenters), including faster recognition of equivalent foreign qualifications and experience. Offering pathways to permanent residency for tradespeople and construction professionals would make Australia a more attractive destination in a globally competitive labour market.

- Expand apprenticeship programs - Programs like subsidies and wage support can incentivize employers to take on apprentices. Removing financial and bureaucratic barriers for small builders to train apprentices (and supporting group training schemes) will help increase the pipeline of local talent. Broadening the funnel of young people entering construction is also key: for example, extending post-study work visas to graduates of vocational programs (Certificate III and above in construction trades), similarly to how university graduates are treated, to encourage more international students in building trades who can then stay and work.

- Rationalise occupational licensing across states - Simplifying and harmonising occupational licensing across states would allow tradespeople to move where the work is without re-certification, improving labour mobility - allowing tradespeople from one state to immediately work in another.

- Long-term workforce planning - Longer-term workforce planning is needed, coordinated between industry and government, to anticipate future demand. This could include partnerships with schools and TAFEs to promote construction careers, upskilling existing workers in new technologies (like modular assembly techniques), and ensuring diversity in recruitment to tap underrepresented groups.

Part two: Scale up social and affordable housing

The market alone cannot deliver secure, affordable housing for all Australians.

Even with reform, private developers can only serve profitable segments, leaving low-income and vulnerable Australians without options. We are now seeing the results of relying too heavily on the private sector: construction is stalling despite strong demand, prices and rents remain high, locking out Australians.

A bold return to government-led delivery – as we have done in past eras – could scale up on-market housing. A renewed social and affordable housing program can stabilise the market, lift quality, and provide a permanent safety net.

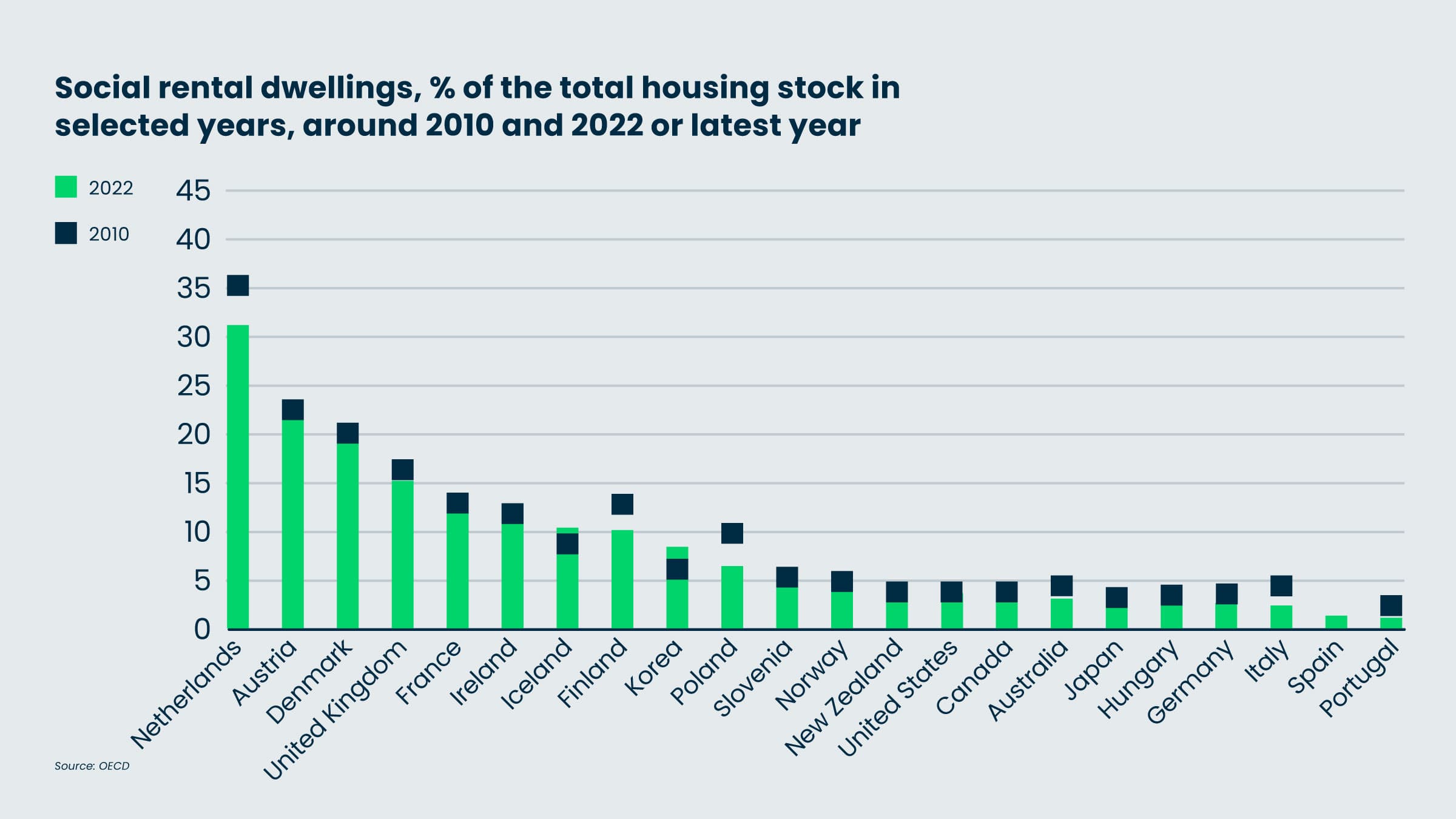

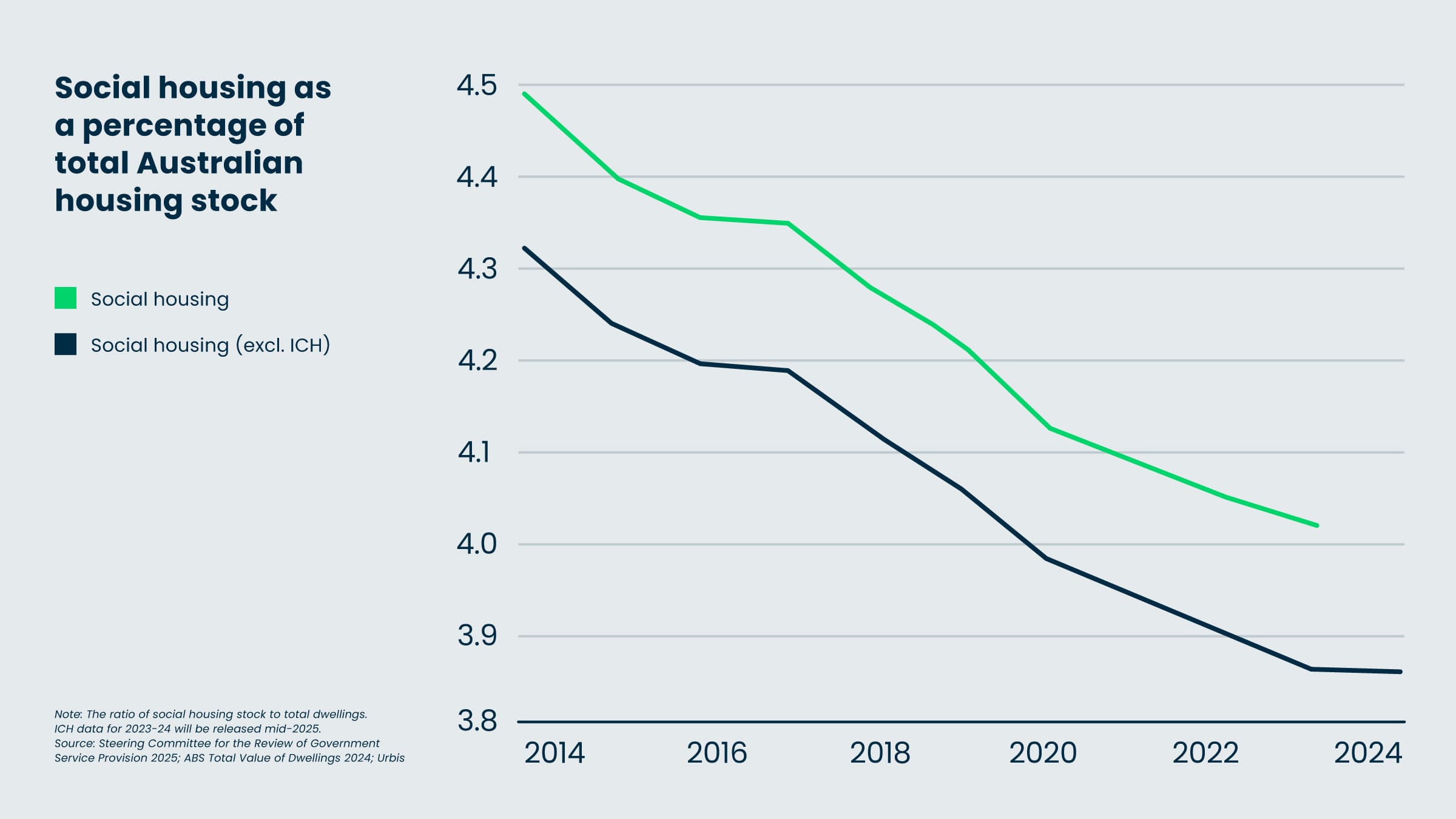

Reframe social and affordable housing

Australia’s public and social housing stock has dwindled to low levels by international standards. Today, only about 3.8% of Australian households live in social housing down from nearly five percent in the 1980s. This is well below the OECD average (roughly 7-8% of housing) and far behind many comparable countries – for example, around 17% of households in England are in social housing, and 24% of Austria’s housing is social housing.

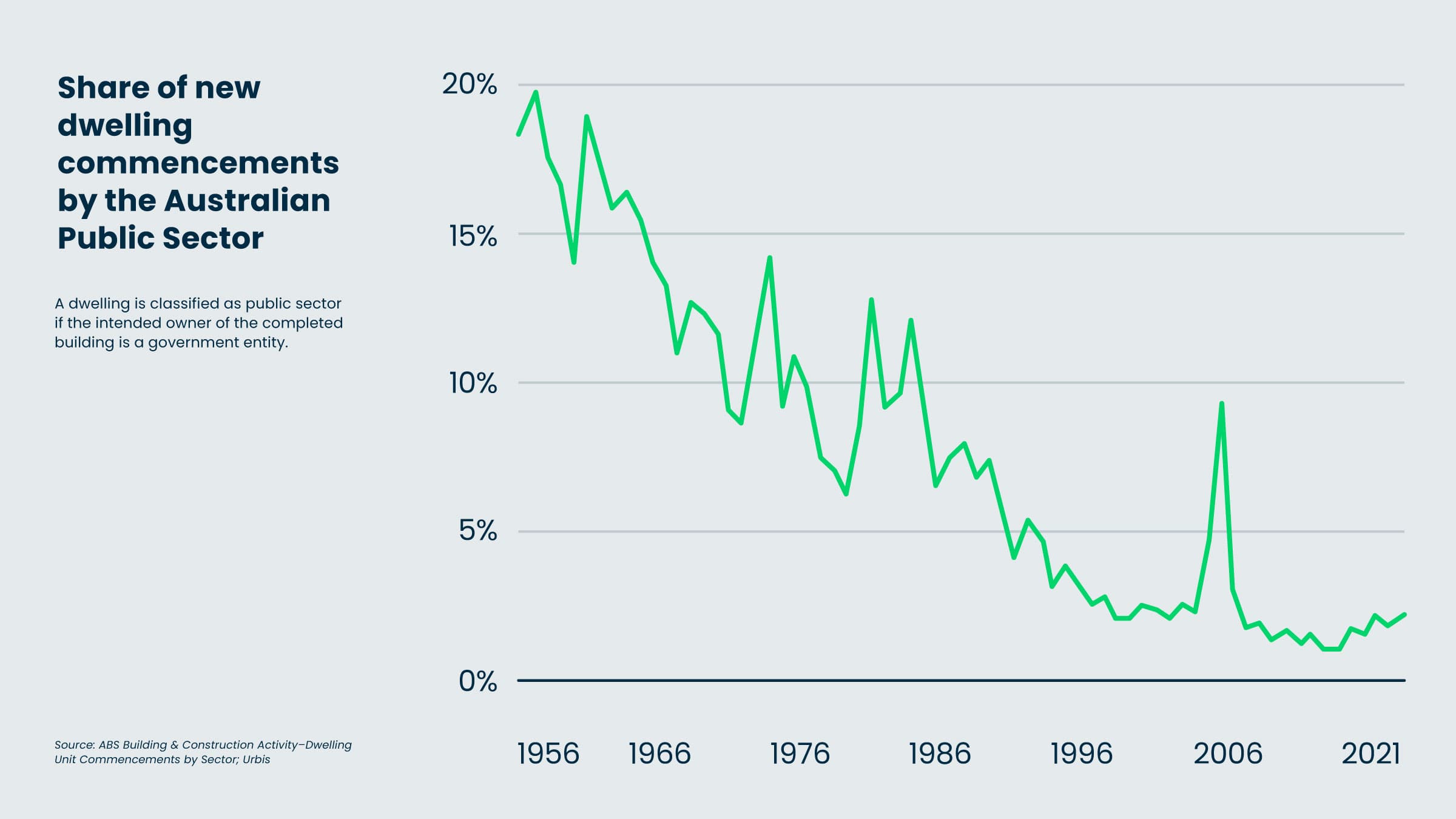

Note: A dwelling is classified as public sector if the intended owner of the completed building is a government entity. Source: ABS Building & Construction Activity–Dwelling Unit Commencements by Sector; Urbis

Consider global exemplars

Leading cities harbour greater ambition: Vienna’s city government owns about 220,000 apartments and directly houses a quarter of the city’s population, while supporting another 200,000 households in cooperatives – meaning over 50% of Viennese residents live in housing that is either publicly built or subsidised.

Singapore offers another example of what scale and vision can achieve: through its Housing & Development Board, Singapore built over a million apartments that now house over 80% of its population, with 90% owning their unit – a scenario that virtually eliminated slums and homelessness in Singapore. These international cases are not presented as direct models for Australia, but as proof of concept that large-scale, government-led housing programs can succeed in providing affordable homes for the majority – comparable to the level of scale and ambition we have possessed in our own not-too-distant past.

In the late 40s and early 50s, Australia embarked on an ambitious public housing program to address acute housing shortages. Under the first Commonwealth-State Housing Agreement (CSHA) from 1945 to 1955, public housing stock nationwide rose from near zero to almost 100,000 dwellings, consisting of 5% of all dwellings. By the end of 1956, over 14% of all dwellings built in Australia were public housing. Then, from 1954 through to the mid-80s, the public sector consistently constructed around 15,000 dwellings per year under successive Commonwealth-State agreements. These were sold to Australians at discounted rates to eligible purchasers.

These models show what scale and ambition can achieve. Australia should aim to deliver hundreds of thousands of new social and affordable housing units over the coming decades. A national program, led by the public sector, supported by the community housing sector and private industry, could maintain a steady pipeline of projects, coordinated by a well-resourced national housing body.

Scale, scale, scale

Small pilot projects offer insight but will not fix the problem: large-scale investment to significantly boost supply and moderate prices. Committing to ambitious targets signals to the market that housing is a national priority. Scale enables productivity: bulk procurement, standardised designs, and steady work for builders. It also sends a message that construction is a stable, valued career path – supporting industry development and workforce growth.

Realise economic benefits

Public housing investment is not just social policy – it is smart economics. It can function as a counter-cyclical stabiliser, keeping builders employed when private activity slows.

This prevents the loss of skilled workers during recessions and allows housing supply to respond to population growth, even while private developers retreat. We have a proof from recent history: during the Global Financial Crisis, the federal government enacted a $5.6 billion Social Housing Initiative (as part of the stimulus) that rapidly delivered around 19,700 new social housing units and refurbished 12,000 more during 2009-12, providing economic stimulus and housing outcomes simultaneously.

Socially, every unit built reduces homelessness and housing stress. It gives families stability to focus on work, health, and education – enabling the autonomy of the least advantaged members of the population. It also eases pressure on the private rental market and reduces downstream costs in health, justice, and social services – making it a form of preventative infrastructure.

Approach financing and partnerships confidently

Australia can afford this – with the political will and support from the private sector. Funding can come from a mix of direct investment, bonds, and potentially public housing trusts. In addition to the successes of the Housing Australia Future Fund, direct investment could treat housing as core infrastructure alongside Medicare, roads, and public schools.

We are seeing this commitment. The federal government has announced that it will reduce barriers to more superannuation investment in new housing supply, which includes supporting ASIC to review RG-97, which industry forecasts show could unlock 35,000 homes and more than $8 billion investment in housing.

Over time, affordable rents and economic dividends will recover some costs. But even if not “self-funding,” the social returns justify the spend. Crucially, what is needed is a consortium approach to delivery — one that brings together government, community housing providers, private developers and financiers. This model can unlock private capital and development capability, supported by enabling regulation and government funding, to deliver a more balanced and consistent housing pipeline.

Such partnerships stretch public investment further, while mechanisms like inclusionary zoning can supplement direct builds. A large public program would also strengthen the private sector – adding supply, moderating price spikes, and offering builders steady contracts. Rather than crowding out the market, it can energise it – much as it did during the post-war boom.

Where to from here?

Australia’s housing crisis is a "wicked problem" – but solvable. Removing constraints on private development and investing directly in social and affordable housing can house more Australians. It is not “either/or” – it is “both/and.”

We have done it before. In the post-war decades, public and private sectors together created suburbs and high ownership rates. Now, we can channel that same ambition – combining private-sector agility with public-sector vision to ensure secure, affordable homes for all. The time to act boldly is now. With clear direction and the courage to invest, we can end this crisis and protect the Australian dream for future generations.